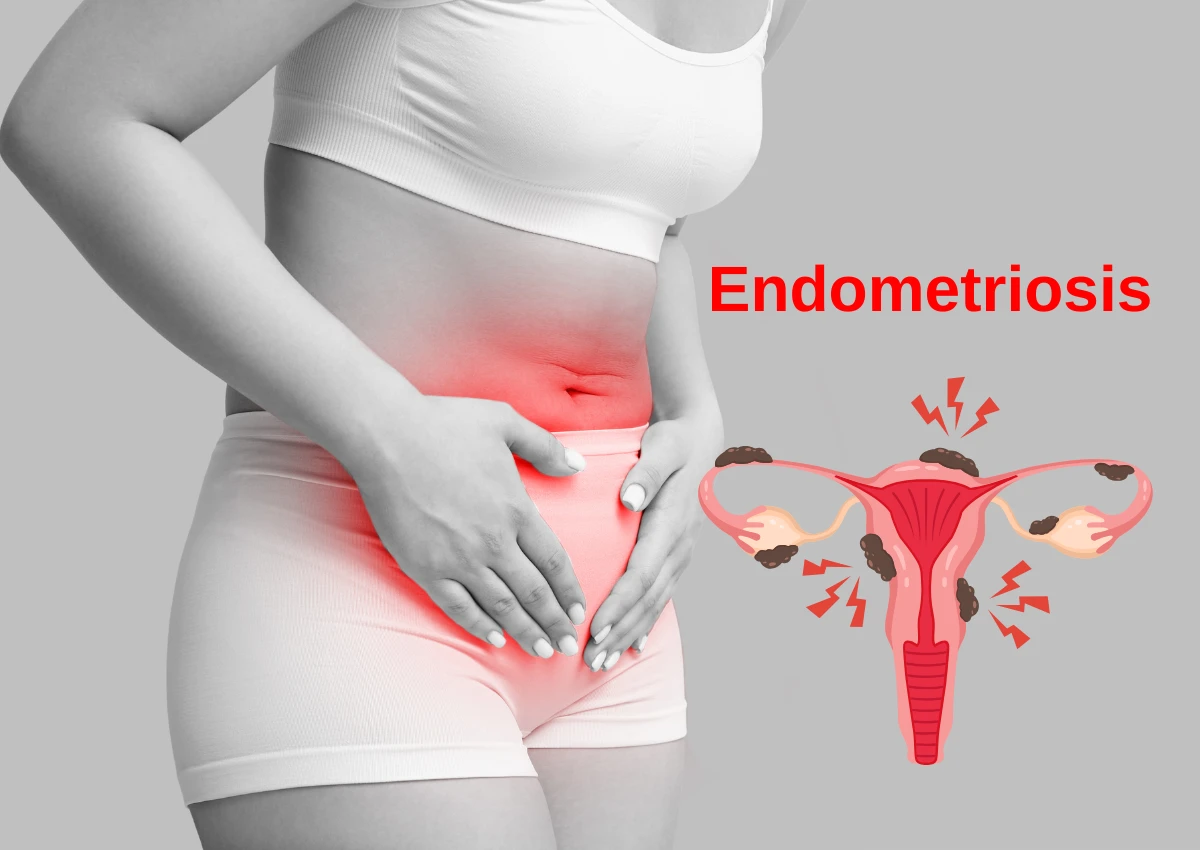

Endometriosis is a chronic condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus—the endometrium—grows outside the uterine cavity, causing inflammation and scarring. Despite its prevalence, determining the exact cause remains a major medical challenge. The condition is classified as idiopathic, meaning no single definitive trigger has been identified. Instead, researchers believe it stems from a multifactorial origin: a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, hormonal imbalances, and immune system dysfunction. Current theories explore mechanisms ranging from retrograde menstruation (backward blood flow) to cellular transformation. Unraveling these potential origins is crucial for understanding why the disease persists and how best to treat it.

Theory 1: Retrograde Menstruation (Sampson’s Theory)

The oldest and most widely accepted explanation is known as Sampson’s Theory of retrograde menstruation. First proposed in the 1920s, this theory suggests a mechanical cause for the disease. During a normal menstrual cycle, the uterine lining sheds and flows out of the body through the cervix. Retrograde menstruation occurs when some of this menstrual blood, containing endometrial cells, flows backward through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity.

Once inside the pelvic cavity, these displaced cells stick to the pelvic walls and the surfaces of organs. Because they are endometrial cells, they continue to function as they would inside the uterus: they thicken, break down, and bleed with every menstrual cycle. However, unlike the lining in the uterus, this blood has no exit route, leading to inflammation and pain.

While this theory is mechanically sound, it has a significant caveat. Studies have shown that retrograde menstruation occurs in approximately 90% of women, yet only about 10% develop endometriosis. This discrepancy suggests that while backward blood flow may deliver the cells, other factors must enable them to survive and grow.

Theory 2: Cellular Transformation (Induction Theory)

Another compelling hypothesis is the Induction Theory. This theory proposes that endometriosis may not be caused by cells moving from one place to another, but by cells transforming in place.

Proponents of this theory suggest that hormones or immune factors can promote the transformation of peritoneal cells—the cells that line the inner side of the abdomen—into endometrial-like cells. This concept helps explain puzzling cases of endometriosis, such as its presence in women who have not yet begun menstruation, or in extremely rare instances, in men undergoing high-dose hormonal treatments.

Theory 3: Embryonic Cell Transformation

Closely related to cellular transformation is the theory of embryonic origins. During fetal development, cells are distributed throughout the body to form various organs. This theory postulates that cells destined to become reproductive tissue are sometimes left behind in the pelvis during development.

These cells remain dormant and immature until puberty. When the body begins producing higher levels of estrogen, these misplaced embryonic cells are stimulated to transform into endometrial tissue implants, effectively “waking up” the disease.

Theory 4: Surgical Scar Implantation

In some cases, the cause of endometriosis is directly linked to medical intervention. This is known as surgical scar implantation. During surgeries such as a Cesarean section (C-section) or a hysterectomy, endometrial cells can be accidentally transferred to the surgical incision.

Once transplanted, these cells attach to the scar tissue of the abdominal wall. Over time, they grow and bleed in sync with the menstrual cycle, causing localized pain and palpable lumps at the incision site. While this accounts for a specific subset of cases, it does not explain endometriosis found deep in the pelvis or on the ovaries.

Theory 5: Transport via Body Systems

One of the most perplexing aspects of endometriosis is its occasional discovery in distant organs, such as the lungs, brain, or eyes. The theory of lymphatic or vascular transport attempts to explain this phenomenon.

According to this theory, the condition spreads in a manner similar to metastasis in cancer (though endometriosis is benign). It suggests that endometrial cells move through the body’s lymphatic system or blood vessels, traveling from the uterus to distant parts of the anatomy where they eventually root and grow.

Theory 6: Immune System Dysfunction

Perhaps the most critical piece of the puzzle lies in the immune system. In a healthy body, the immune system acts as a scavenger; it identifies misplaced tissue or debris and destroys it. If endometrial cells flow backward into the pelvis, a robust immune system should technically recognize them as “out of place” and eliminate them.

Researchers believe that women with endometriosis may suffer from a specific immune dysfunction. In these individuals, the immune system fails to recognize the stray cells or is unable to destroy them effectively. This failure allows the cells to implant, grow, and develop into the chronic lesions that characterize the disease.

Contributing Risk Factors

While these theories explain the mechanisms, genetics and hormones provide the fuel. There is a strong genetic link to the disease; a woman is much more likely to develop endometriosis if her mother or sister has it. Furthermore, the condition is estrogen-dependent. High lifelong exposure to estrogen—such as starting menstruation at an early age or entering menopause late—appears to increase the risk and severity of the condition.

Comments

comments